The Story of Patriarchs and Prophets

by Ellen G. White

Chapter 16: Jacob and Esau

|

|

For wild pleasure, miscalled freedom, how many are still selling their

birthright to an inheritance pure and undefiled, eternal in the heavens!

Illustration ©

Review and Herald Publ. Assoc. |

|

Jacob and Esau, the twin sons of Isaac, present a striking

contrast, both in character and in life. This unlikeness was

foretold by the angel of God before their birth. When in answer

to Rebekah's troubled prayer he declared that two sons would be

given her, he opened to her their future history, that each would

become the head of a mighty nation, but that one would be

greater than the other, and that the younger would have the

pre-eminence.

Esau grew up loving self-gratification and centering all his

interest in the present. Impatient of restraint, he delighted in the

wild freedom of the chase, and early chose the life of a hunter.

Yet he was the father's favorite. The quiet, peace-loving shepherd

was attracted by the daring and vigor of this elder son, who

fearlessly ranged over mountain and desert, returning home with

game for his father and with exciting accounts of his adventurous

life. Jacob, thoughtful, diligent, and care-taking, ever thinking

more of the future than the present, was content to dwell at

home, occupied in the care of the flocks and the tillage of the

soil. His patient perseverance, thrift, and foresight were valued

by the mother. His affections were deep and strong, and his

gentle, unremitting attentions added far more to her happiness

than did the boisterous and occasional kindnesses of Esau. To

Rebekah, Jacob was the dearer son.

The promises made to Abraham and confirmed to his son

were held by Isaac and Rebekah as the great object of their desires

and hopes. With these promises Esau and Jacob were familiar.

They were taught to regard the birthright as a matter of great

importance, for it included not only an inheritance of worldly

wealth but spiritual pre-eminence. He who received it was to

be the priest of his family, and in the line of his posterity the

Redeemer of the world would come. On the other hand, there

were obligations resting upon the possessor of the birthright. He [p. 178] who should inherit its blessings must devote his life to the service

of God. Like Abraham, he must be obedient to the divine requirements.

In marriage, in his family relations, in public life, he

must consult the will of God.

Isaac made known to his sons these privileges and conditions,

and plainly stated that Esau, as the eldest, was the one entitled to

the birthright. But Esau had no love for devotion, no inclination

to a religious life. The requirements that accompanied the spiritual

birthright were an unwelcome and even hateful restraint to

him. The law of God, which was the condition of the divine

covenant with Abraham, was regarded by Esau as a yoke of bondage.

Bent on self-indulgence, he desired nothing so much as liberty

to do as he pleased. To him power and riches, feasting and

reveling, were happiness. He gloried in the unrestrained freedom

of his wild, roving life. Rebekah remembered the words of the

angel, and she read with clearer insight than did her husband the

character of their sons. She was convinced that the heritage of

divine promise was intended for Jacob. She repeated to Isaac the

angel's words; but the father's affections were centered upon the

elder son, and he was unshaken in his purpose.

Jacob had learned from his mother of the divine intimation

that the birthright should fall to him, and he was filled with an

unspeakable desire for the privileges which it would confer. It

was not the possession of his father's wealth that he craved; the

spiritual birthright was the object of his longing. To commune

with God as did righteous Abraham, to offer the sacrifice of

atonement for his family, to be the progenitor of the chosen people

and of the promised Messiah, and to inherit the immortal

possessions embraced in the blessings of the covenant-here were

the privileges and honors that kindled his most ardent desires.

His mind was ever reaching forward to the future, and seeking

to grasp its unseen blessings.

With secret longing he listened to all that his father told

concerning the spiritual birthright; he carefully treasured what he

had learned from his mother. Day and night the subject occupied

his thoughts, until it became the absorbing interest of his life.

But while he thus esteemed eternal above temporal blessings,

Jacob had not an experimental knowledge of the God whom

he revered. His heart had not been renewed by divine grace. He

believed that the promise concerning himself could not be fulfilled [p. 179] so long as Esau retained the rights of the first-born, and he

constantly studied to devise some way whereby he might secure

the blessing which his brother held so lightly, but which was so

precious to himself.

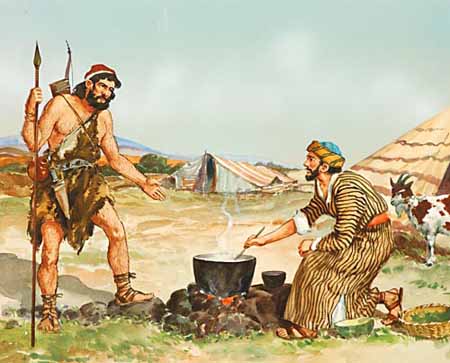

When Esau, coming home one day faint and weary from the

chase, asked for the food that Jacob was preparing, the latter,

with whom one thought was ever uppermost, seized upon his

advantage, and offered to satisfy his brother's hunger at the price

of the birthright. "Behold, I am at the point to die," cried the

reckless, self-indulgent hunter, "and what profit shall this

birthright do to me?" And for a dish of red pottage he parted with

his birthright, and confirmed the transaction by an oath. A short

time at most would have secured him food in his father's tents,

but to satisfy the desire of the moment he carelessly bartered the

glorious heritage that God Himself had promised to his fathers.

His whole interest was in the present. He was ready to sacrifice

the heavenly to the earthly, to exchange a future good for a

momentary indulgence.

"Thus Esau despised his birthright." In disposing of it he felt

a sense of relief. Now his way was unobstructed; he could do as

he liked. For this wild pleasure, miscalled freedom, how many

are still selling their birthright to an inheritance pure and

undefiled, eternal in the heavens!

Ever subject to mere outward and earthly attractions, Esau

took two wives of the daughters of Heth. They were worshipers

of false gods, and their idolatry was a bitter grief to Isaac

and Rebekah. Esau had violated one of the conditions of the

covenant, which forbade intermarriage between the chosen people

and the heathen; yet Isaac was still unshaken in his determination

to bestow upon him the birthright. The reasoning of Rebekah,

Jacob's strong desire for the blessing, and Esau's indifference to

its obligations had no effect to change the father's purpose.

Years passed on, until Isaac, old and blind, and expecting

soon to die, determined no longer to delay the bestowal of the

blessing upon his elder son. But knowing the opposition of

Rebekah and Jacob, he decided to perform the solemn ceremony in

secret. In accordance with the custom of making a feast upon

such occasions, the patriarch bade Esau, "Go out to the field, and

take me some venison; and make me savory meat, . . . that my

soul may bless thee before I die." [p. 180]

Rebekah divined his purpose. She was confident that it was

contrary to what God had revealed as His will. Isaac was in danger

of incurring the divine displeasure and of debarring his

younger son from the position to which God had called him. She

had in vain tried the effect of reasoning with Isaac, and she

determined to resort to stratagem.

No sooner had Esau departed on his errand than Rebekah set

about the accomplishment of her purpose. She told Jacob what

had taken place, urging the necessity of immediate action to

prevent the bestowal of the blessing, finally and irrevocably, upon

Esau. And she assured her son that if he would follow her directions,

he might obtain it as God had promised. Jacob did not

readily consent to the plan that she proposed. The thought of

deceiving his father caused him great distress. He felt that such

a sin would bring a curse rather than a blessing. But his scruples

were overborne, and he proceeded to carry out his mother's

suggestions. It was not his intention to utter a direct falsehood, but

once in the presence of his father he seemed to have gone too far

to retreat, and he obtained by fraud the coveted blessing.

Jacob and Rebekah succeeded in their purpose, but they gained

only trouble and sorrow by their deception. God had declared

that Jacob should receive the birthright, and His word would

have been fulfilled in His own time had they waited in faith

for Him to work for them. But like many who now profess

to be children of God, they were unwilling to leave the matter

in His hands. Rebekah bitterly repented the wrong counsel she

had given her son; it was the means of separating him from

her, and she never saw his face again. From the hour when

he received the birthright, Jacob was weighed down with

self-condemnation. He had sinned against his father, his brother,

his own soul, and against God. In one short hour he had made

work for a lifelong repentance. This scene was vivid before him

in afteryears, when the wicked course of his sons oppressed

his soul.

No sooner had Jacob left his father's tent than Esau entered.

Though he had sold his birthright, and confirmed the transfer by

a solemn oath, he was now determined to secure its blessings,

regardless of his brother's claim. With the spiritual was connected

the temporal birthright, which would give him the headship of

the family and possession of a double portion of his father's [p. 181] wealth. These were blessings that he could value. "Let my father

arise," he said, "and eat of his son's venison, that thy soul may

bless me."

Trembling with astonishment and distress, the blind old father

learned the deception that had been practiced upon him. His

long and fondly cherished hopes had been thwarted, and he

keenly felt the disappointment that must come upon his elder

son. Yet the conviction flashed upon him that it was God's

providence which had defeated his purpose and brought about the

very thing he had determined to prevent. He remembered the

words of the angel to Rebekah, and notwithstanding the sin of

which Jacob was now guilty, he saw in him the one best fitted

to accomplish the purposes of God. While the words of blessing

were upon his lips, he had felt the Spirit of inspiration upon

him; and now, knowing all the circumstances, he ratified the

benediction unwittingly pronounced upon Jacob: "I have blessed

him; yea, and he shall be blessed."

Esau had lightly valued the blessing while it seemed within

his reach, but he desired to possess it now that it was gone from

him forever. All the strength of his impulsive, passionate nature

was aroused, and his grief and rage were terrible. He cried with

an exceeding bitter cry, "Bless me, even me also, O my father!"

"Hast thou not reserved a blessing for me?" But the promise

given was not to be recalled. The birthright which he had so

carelessly bartered he could not now regain. "For one morsel of

meat," for a momentary gratification of appetite that had never

been restrained, Esau sold his inheritance; but when he saw his

folly, it was too late to recover the blessing. "He found no place of

repentance, though he sought it carefully with tears." Hebrews

12:16, 17. Esau was not shut out from the privilege of seeking

God's favor by repentance, but he could find no means of

recovering the birthright. His grief did not spring from conviction

of sin; he did not desire to be reconciled to God. He sorrowed

because of the results of his sin, but not for the sin itself.

Find out more today how to get a special discount when you purchase a

hardcover or

paperback

copy of Patriarchs and Prophets.

|

|

Because of his indifference to the divine blessings and

requirements, Esau is called in Scripture "a profane person." Verse

16. He represents those who lightly value the redemption purchased

for them by Christ, and are ready to sacrifice their heirship

to heaven for the perishable things of earth. Multitudes live

for the present, with no thought or care for the future. Like Esau [p. 182] they cry, "Let us eat and drink; for tomorrow we die." 1

Corinthians 15:32. They are controlled by inclination; and rather

than practice self-denial, they will forgo the most valuable

considerations. If one must be relinquished, the gratification of a

depraved appetite or the heavenly blessings promised only to the

self-denying and God-fearing, the claims of appetite prevail, and

God and heaven are virtually despised. How many, even of professed

Christians, cling to indulgences that are injurious to health

and that benumb the sensibilities of the soul. When the duty is

presented of cleansing themselves from all filthiness of the flesh

and spirit, perfecting holiness in the fear of God, they are

offended. They see that they cannot retain these hurtful gratifications

and yet secure heaven, and they conclude that since the

way to eternal life is so strait, they will no longer walk therein.

Multitudes are selling their birthright for sensual indulgence.

Health is sacrificed, the mental faculties are enfeebled, and heaven

is forfeited; and all for a mere temporary pleasure—an indulgence

at once both weakening and debasing in its character. As Esau

awoke to see the folly of his rash exchange when it was too late to

recover his loss, so it will be in the day of God with those who

have bartered their heirship to heaven for selfish gratifications.

Click here to read the next chapter:

"Jacob's Flight and Exile"

|